Preface

Open source licenses have

evolved from the original GPL to GPLv2 and GPLv3, along with Apache, MPL, AGPL, LGPL, etc. But a

number of new licenses have emerged in recent years, causing some heated discussions in the

community. These new licenses include BSL, SSPL, Elastic, and a special addition called Commons

Clause.

The community is mainly

divided into two camps from the perspective of argument: Fundamentalism and Pragmatism.

Fundamentalist followers

believe that only those who comply with the 10 principles defined by the Open Source Initiative

(OSI) established in 1998 and pass the OSI certification (get OSI-Certified) can be called

open source licenses.

Pragmatism, starting from the

purpose of open source itself, believes that under the condition that the source code is open and

the vast majority of community developers can use or contribute without being affected, there is no

need to struggle with the literal definition, as long as it can be beneficial to the community.

According to the OSI open

source License rules, currently, MongoDB using SSPL, Elastic Search and Airbyte using Elastic

License V2, CockroachDB using BSL, and Redis with Common Clause, all these famous open source

software could not be called “open source software”.

So here comes the question.

If these software are not considered open source but proprietary software due to above reasons,

should we really call these software that we have been using for free for a long time and can

continue to use well as “closed source software” or “commercial software”? It doesn’t seem right

either. “Source code available”? Sounds a little bit detour.

Let’s firstly look at some of

the underlying logic of the two opposing sides of this problem from the perspective of the new

generation of open source software vendors represented by SSPL and the OSI. Finally, let’s share

some views about open source licenses in the cloud era.

SSPL as I know it

MongoDB is a very popular

NoSQL database for programmers. I came into contact with it when I started a business with my

friends in Silicon Valley around 2012. After spending a weekend rewriting thousands of lines of

Python code and changing my interaction with MySQL to MongoDB, my intention was to improve

concurrency and I found an unexpected surprise: The number of lines of code was reduced to a few

hundred, 15% of its original size. From then on, I started my NoSQL journey without any hesitation.

Because I was active in the

community and also wrote an open source NodeJS component related to MongoDB, so I joined MongoDB

after the startup project stopped in 2013. When I joined, MongoDB had been established for 6 years

and had 300 to 400 employees. The annual expenditure was $100 million. How about the revenue? At

that time, MongoDB’s main revenue came from consulting services and selling the enterprise version.

However, revenues from consulting service are meagre, the enterprise version is not very easy to

sell. The biggest competitor was itself: the open source version. Therefore, it could only rely on a

large amount of venture capital for continuous “blood transfusion”. However, the financing has

reached the round F, and the patience of investors is finally exhausted. After a board meeting, CEO

and CRO were all removed and replaced with a veteran professional manager, Dev Ittycheria.

Dev immediately set a target

of going public in 2-3 years, and implemented a series of new commercialization initiatives,

including making commercialization the top priority, going global, launching cloud version products

and a series of other measures. It was at that time that I returned to China from the United States

where I had lived and worked for more than 10 years. As the first official employee of MongoDB in

Greater China, my job was to help MongoDB to commercialize in China. In the second half year of 2014

when I returned to China, MongoDB cloud product Atlas was still under development, and the main

commercialization method of MongoDB was still the enterprise version.

In 2016, MongoDB officially

released Atlas, a managed database service on the public cloud. Numbers of the customers of MongoDB

Enterprise could be hundreds or thousands, but there may be hundreds of thousands of developers of

the open source version. Most of these developers would not buy the enterprise license, but they

need to use, manage and maintain the database anyway. At this time, Atlas, a form of cloud product,

quickly gained the favor of these developers. Although the cost was not too low, after all, it was

used out of the box, saving cost for 0.5 or 0.25 DBA . Therefore, MongoDB Atlas has shown a

relatively rapid growth since it was released, and became the fastest growing business of MongoDB

when it went public in 2017.

On the other hand, one of the

public cloud vendors in China also launched MongoDB as a Service using the community version based

on AGPL on their public cloud in 2016, earlier than MongoDB company. In the Chinese market at that

time, the sales of the enterprise version was actually struggling. The sales logic of the enterprise

version was to provide additional value, mainly including the technical support from MongoDB company

and a set of independent additional cluster management tools (monitoring, backup, etc.). There was

no difference on capacity of MongoDB server between the enterprise version and open source version.

However, in terms of the software acquisition cost, one is zero and the other is hundreds of

thousands of RMB per year. At that time, in the Chinese enterprise market where it cost 100,000 RMB

to hire an engineer, it’s easy to imagine how high the willingness of enterprises to pay for

enterprise version.

In addition to China, some

top cloud vendors in Russia also began to launch MongoDB as a Service on their cloud, which was also

based on the free MongoDB community edition. In this process, cloud vendors are bound to make many

changes to the source code in order to better integrate a product into their unified cloud

management platform, provide some additional capability support, or solve some product bugs to meet

the SLA by themselves. At this time, MongoDB found that some cloud vendors did not fully comply with

the AGPL protocol specifications, that is, they didn’t open source all these changes.

The actual practice of cloud

merchants is often this way. Firstly, fork an upstream version of MongoDB publicly, and then

symbolically commit some updates to GitHub within that fork. In fact, a lot of development will take

place on a private fork and won’t be pushed onto the public fork, let alone backported to the

upstream. From the perspective of MongoDB, when it was found that these AGPL agreements were not

well implemented in these cloud vendors, it tries to communicate with the cloud vendors from the

commercial perspective, hoping that the other side will either publish the code according to the

protocols of the industry, or reach a commercial cooperation.

After several consultations

and invloving of their respective Legal teams, MongoDB found that the problem it was facing was that

the expectations of both sides were too different for commercial cooperation. One wanted deep

cooperation, while the other was only willing to share only a tiny fraction of the benefits. In

terms of open source compliance, the cloud vendors point to the repository which was barely updated

and said that we had opened source according to the agreement. You couldn’t go to internal forensics

until you go to court. What should MongoDB company do? There’s no precedent for similar cases. It

sounds like a rough road to follow this path in a completely strange country. However, cloud service

was the most important revenue growth engine of almost every new generation open source software

companies, and it was really impossible to leave it alone.

So MongoDB chose a drastic

measure to deal with this situation. That was changing the license (as we all knew later).

Before the change, MongoDB

mainly adopted the AGPL license. This is an OSI certified and universally recognized standard open

source license type. In order to cope with the difficulties encountered by cloud vendors, MongoDB

has added a supplementary clause based on AGPL protocol:

Art. 13: If you use the software to sell the software itself directly on the public cloud in the form of “XXX as a Service”, then you need to open source all relevant changes, including the background management platform software that supports the use of the software.

So, in a nutshell, SSPL is

equal to AGPL + Art. 13 amendment. Once you understand the original intention, purpose and impact

scope of this amendment, you also understand the essence of SSPL.

-

Original intention: to compete with cloud vendors in the interests of commercialization.

-

Purpose: To prevent such third parties who use open source software to profit directly but do not follow the rules of the game.

-

Impact scope: Public cloud vendors that directly provide open source software AS a Service

After the official release of

SSPL, the immediate effect was obvious: cloud vendors either went offline or entered into commercial

partnerships with original vendors to obtain special licenses to continue providing MongoDB as a

Service.

And, of course, the impact

was profound — leading to a huge turbulence in the open source community. The controversy over

whether the software using new licenses such as SSPL and later Elastic License V2 can be called

“open source software” has filled the technology social network for a while. Many extreme views

believe that if such open source mode is accepted, open source will gradually perish. There are also

arguments that adopting such a “quasi-open source” license would trigger a huge backlash from the

community, and it wouldn’t take more than 2-3 years for these companies to collapse (these

discussions almost appeared on 2018).

OSI Certified

Let’s take another look at

OSI, the guardian of open source software standards.

When we say whether a

software can be called “open source software”, it is strictly said that the software can be called

“open source software” if it uses a OSI certified license. Conversely, if the license used is not on

the OSI Certified list, then the software probably should not be called “open source software.”

Some of the most common OSI

Certified licenses are:

-

MIT

-

BSD

-

Apache

-

MPL

-

GPL

-

LGPL

-

AGPL

-

…

It’s worth noting that this

definition is more like community’s self-restraint than a legal one. According to the OSI itself,

the word “open source” is not a registered trademark, so theoretically anyone can use it. You cannot

legally prevent a software from calling itself “open source” even if it’s not approved by the OSI.

However, we are all in the

same ecology. The ecology is made up of various members. Here, beyond the legal jurisdiction, there

are more conventions and standardization organizations in the industry. OSI is an organization set

up to encourage and promote the vigorous development of open source software. Just imagine that

without OSI’s rigorous procedures of reviewing licenses, defining the scope of safe use of software,

and providing authoritative explanations, there would be various and varied of licenses on the

market. For the vast majority of the open source community and users of open source software, this

will be a huge cost of cognitive and risk. If you use an obscure license and don’t get a lawyer to

review it carefully, and just integrate the code into your product because it works, the day you get

a little bit of success is the day you receive a letter from the opposing lawyer.

From this point of view, we

need organizations like OSI, as well as the OSI Certified licensing mechanism. This is not a

restriction, the purpose is to help the community users remove the hidden risk of using open source

software, in order to protect the better development of the open source community.

This is why, after MongoDB

announced SSPL, Elliot, the CTO of MongoDB, submitted an application for SSPL certification to OSI,

hoping that OSI would approve it and make SSPL a Certified license. (MongoDB quickly withdrew the

application, however, because OSI had already previewed SSPL’s death on social media before the

formal review process began. MongoDB believed it was impossible to ensure a fair review process

under such circumstances.)

Let’s take a look at the

recognition principles of OSI for current open source licenses. According to OSI, whether a license

is open source depends on whether it meets the 10 requirements of the Open Source Definition (OSD [1] ):

-

Free Redistribution

-

Source Code

-

Derived Works

-

Integrity of The Author’s Source Code

-

No Discrimination Against Persons or Groups

-

No Discrimination Against Fields of Endeavor

-

Distribution of License

-

License Must Not Be Specific to a Product

-

License Must Not Restrict Other Software

-

License Must Be Technology-Neutral

Criticism of SSPL focuses on

Rule 9: licenses cannot bind other software. The terms of SSPL will trigger restrictions on other

software (cloud management platform software) of developers when developers (public cloud vendors)

try to directly sell Mongodb as a Service (note that is’s selling the database service itself, not

the derivative service).

Therefore, according to the

existing conventions, such licenses as SSPL/Elastic do not meet the open source standard of OSI. So

MongoDB, Elastic, etc., do respect this consensus of community by not calling themselves open

source, but “source code available.”

As a non-profit operator of

the MongoDB Chinese community, we recently conducted a little survey to see how the developers and

users, the main members of the community , view these issues.

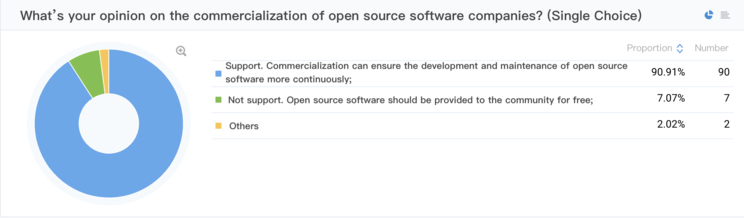

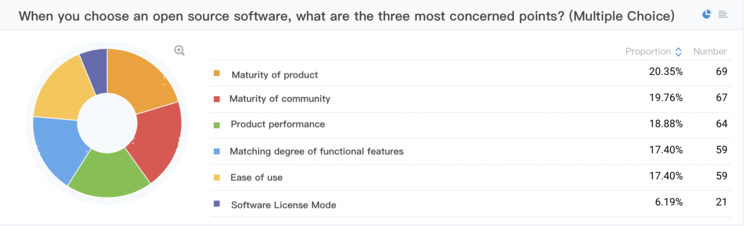

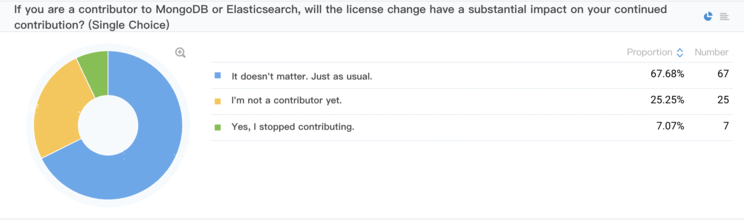

Mongodb Chinese community license questionnaire survey results

In half a day, we collected

99 valid answers. The following are some of the survey results:

Here are some summaries of

the data which can provide some observations:

-

91% of the users here support commercialization of open source software , 7% do not support it, and 2% others.

-

The code contributors of open source software only account for 8%, and the rest can be understood as users. In other words, the vast majority of the open source community are users of open source software.

-

When it comes to choosing open source software, only 6% of the users said that the license model of the software is an relatively important consideration.

-

As many as 73% of the users say SSPL/Elastic’s change to cloud vendors was reasonable and supportive, 10% said it doesn’t matter and 17% opposed it.

-

For open source software users, 89% of the users said the license change had no impact on their continued use of the software.

-

For contributors to open source software, 7% of the users stopped contributing due to license changes.

How should we rationally view open source licenses in the cloud era?

After some discussion of SSPL

and OSI Certified and some community surveys, let’s return to our core question:

How should we view

these new open source licenses in the cloud age?

Considering the original

intention of software vendors such as MongoDB, Elastic and Redis to modify their licenses, they are

actually looking for a solution against unfair competition from public cloud vendors. Therefore, we

say that this problem only exists in the cloud era.

Let me start with a list of

facts and opinions that are not too controversial:

-

MongoDB, Elastic, and Redis are all mainstream open source software vendors that have achieved great success.

-

The continuous and healthy development of these software can still serve the vast majority of open source community users (89%) regardless of OSI’s attitude.

-

The modification of the open source licenses of these companies is a response to the rolling business competition of cloud vendors.

-

Open source communities need to be inclusive, just as established rules include non-discrimination against individuals and groups.

-

OSI’s 10 open source rules were established more than 20 years ago, before the emergence of public cloud, which is a cross-era form.

-

One of the greatest significance of OSI is to develop standards that help community users define the boundaries of different open source licenses.

-

Open source software pursuing commercialized is still a reasonable part of the open source community.

-

Community users support the commercialization of open source software (91%).

-

We do not like monopoly and arbitrary. We like the ecology to thrive and encourage innovation.

Under the above basic

viewpoints, I would like to share some of my opinions:

① MongoDB/Elastic/Redis

represents open source technology companies. Their characteristics are that they open their code in

the form of a technologically innovative company, spread their products through the open source

community, and absorb the contributions and feedback while providing the community with excellent

software which can be obtained for free, and serve their own commercialization demands.This kind of

‘For-profit’ open source has its own unique advantages over open source software that is not

supported by a commercial company: clear product path (developers can plan with confidence), rapid

technology iteration (there are enough excellent engineers for full-time research and development),

and security issues or major bugs can be guaranteed to be resolved.

② When OSI was born more than

20 years ago, the open source community was mostly hobbist with individual contributors as the

mainstream. Now, most open source communities are composed of developers (users) rather than

contributors. Developers’ awareness of the scientific definition of a term is relatively low (6% of

developers are concerned about the content of the license). Conversely, excellent performance,

functionality and maturity are the primary concerns of community users.

③ As a community oriented

organization, OSI needs to look at new things from the perspective of development. If it’s really

for the sake of the community users, OSI could do something based on community voting to sbsorb

feedback from the community and work together to revise the 20-year-old regulation

to accommodate some licenses with commercially considerations into the big family of open source.

For example, open source software can be classified from different dimensions, licenses with

commercialization demands can be put into a separate category, and some common compliance terms can

be clearly explained and reviewed to help people correctly adopt appropriate open source software.

It can even be considered that as long as the software code is open source and available for free,

the remaining restrictive terms and conditions can be divided into Level 1, 2 and 3, from ‘Most

Permissive’ to ‘Most Restrictive’. You can use open source software at the corresponding level as

needed. Only in this way can we truly serve the community, rather than a standard organization that

“operates under the sponsorship of institutions and is influenced by some minorities with strong

opinions”.

④ For the vast majority of

users, as well as contributors, you need to understand the original intention behind the emergence

of these new licenses in the cloud era. Just like when we select technologies scientifically, we all

know that we can’t just listen to the voice of the market, but ultimately see whether it is suitable

for our own business scenario.If the changes of these licenses have no impact on your scenario (a

simple judgment: whether you are a public cloud vendor or not, if not, the probability is that these

seems no change for you), you can completely accept these new “source code available” licenses.

Our practice at TapData

After leaving MongoDB, I

founded TapData. Inc. and have great expectations for our company, hoping that we will become a

company with a strong sense of mission – enabling enterprises to use real-time data more easily and

at lower cost to bring greater business value. Make Data on Tap.

After three years of

developing and online verification by dozens of customers, TapData has become a real-time data

platform with full link real-time as the core technology capability stack, and it is also the first

real-time heterogeneous data integration platform supporting more than 50 data sources.

To achieve our mission, we

found that reducing the cost of access to TapData and encouraging community dissemination are the

most effective means in this era. So we recently officially opened the source code on Github and

established the TapData open source project.

-

GitHub: github.com/tapdata/tapdata

-

Slack: tapdatacommunity.slack.com

TapData open source project

uses a mixed license model. Our strategy is to use Apache V2 license for those community

contributors who use our Plugin Development Kit to develop various data sources and data computing

plug-in codes, while the core engine framework developed by TapData open source team, including data

type standardization, stream computing engine, self-developed operators and UDF capabilities, will

use SSPL license mode.

We hope to continuously

provide community developers and our customers with the best data products based on the TapData open

source project’s pioneering and leading advantages in real-time data field, strong product

capabilities and effective commercialization methods.

Finally, I quote Thomas

Kurian, CEO of Google Cloud, for his

attitude towards open source software, to prove that in the cloud era, we need an

ecosystem of common development, rather than the outcome that For-profile open source software

cannot survive because of the asymmetric competitive advantages of cloud vendors[2].

“The most important thing is that we believe that the platforms that win in the end are those that enable rather than destroy ecosystems…… In order to sustain the company behind the open-source technology, they need a monetization vehicle. If the cloud provider attacks them and takes that away, then they are not viable and it deteriorates the open-source community.”

Open source license,

welcome to the cloud era!

Reference

[1]

https://opensource.org/osd

[2]

https://techcrunch.com/2019/04/09/google-clouds-new-ceo-on-gaining-customers-startups-supporting-open-source-and-more/